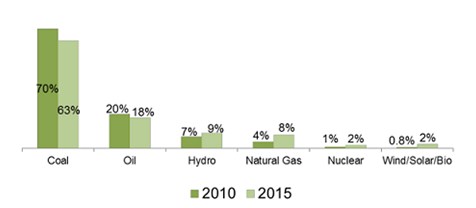

Global warming and carbon emissions have strongly shaped policies around the world during the past decade. Today most governments around the world see it as their goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. When China surpassed the US in carbon emission in 2006 the country came into the spotlight of carbon and renewable energy discussions with the country’s energy consumption relying greatly on fossil fuels. Currently, China’s energy supply is dominated by coal consumption, while natural gas and oil are in relative short supply. In 2007 fossil fuels accounted for more than 90 percent of China’s energy consumption, of which roughly 75 percent came from coal. [1] This is largely the result of coal being China’s most abundant fossil energy resource with an estimated 5,570 billion tonnes in coal deposits located within the country, making up roughly 12.6 percent of the world’s total coal reserves. [2] Despite its abundant reserves China became a net importer of coal in 2009.

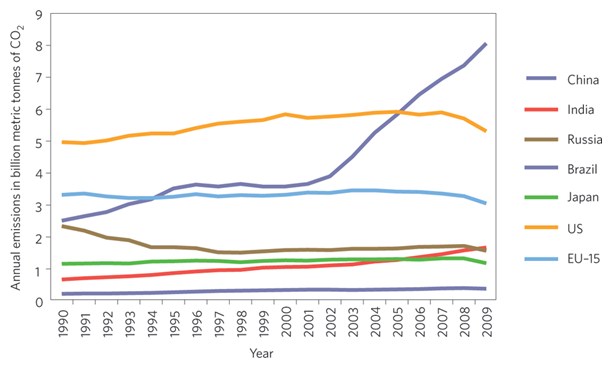

China also overtook the United States in 2009 to become the world’s largest energy user and as a by-product also became the leader in greenhouse gas emissions. In 2011 China was estimated to emit more CO2 than the US and Canada together, an increase of 171 percent since the year 2000.[3]

It is widely recognized that China has to play a key role in tackling worldwide greenhouse gas emissions and global warming. Whereas China’s emissions are still increasing rapidly we observe that the US and European emissions have decreased during recent years. Nevertheless, China’s per capita emissions are still far lower than that of its rivalling western counterparts. In 2006 China’s carbon dioxide emissions equalled to the worlds average and were less than 25 percent of American emissions. Figure 2 below shows the per capita energy related CO2 emissions in 2006.

Whilst China’s per capita emissions do not yet rival that of its western counterparts, prospects for growth remain strong. Given that China’s relatively low per capita consumption level, it is expected that with the country’s continued economic growth and urbanisation, the per capita emissions and total emissions are still going to increase significantly. According to the International Energy Agency, China is expected to contribute 36 percent to the projected growth in global energy use, with its demand rising by 75 percent between 2008 and 2035. [6]

With increasing energy consumption China is also increasingly facing severe pollution problems. The coal dominated energy consumption leads to serious environmental pollution in China. As shown in Fig. 2, between 1983 and 2005 the acid rain-polluted area has extended greatly to about 1.5 million square kilometres in China. Over 10 percent cities in 20 provinces have been affected by acid rain so far. [7] Figure 3 on the following page shows the development of China’s acid rain profile during the past three decades.

In addition to the problem of increased CO2 production and pollution that China faces there is also the issue of energy security. With China having transmitted from being a net exporter to a net importer of coal in 2007, energy security has become a top priority for the Chinese government. Security of energy supply, increasing energy demand, the emission of greenhouse gases and pollution has compelled the Chinese government to turn to renewable energy.

Facing those challenges China is well aware that vigorous government-led change is necessary, knowing that the future of renewables “hinges critically on strong government support to make renewables cost-competitive with other energy sources and technologies, and to stimulate technological advances.”[9] As one of the most proven forms of economically sustainable renewable energy, wind power has been embraced by Chinese policy makers. Unlike conventional energy sources, wind energy does not rely on fossil fuels once assembled and China has been found to have abundant wind resources with its large land mass and expansive coastline. This essay will focus on China’s policies regarding wind power, preceded by a brief overview of China’s wind potential and followed by a discussion of policy issues and general barriers that China is facing with wind power.

China Wind Potential

According to the estimates by China Meteorological Administration, China’s onshore technically feasible wind resources are estimated to be around 1000 GW with China’s offshore potential estimated to be roughly 300GW. To put this into perspective, China’s technically feasible wind resources equate to 1300 standard atomic power plants with 1000MW output power. Figure 4 below shows the wind density across China measured by the CMA Wind and Solar Energy Resources Assessment Centre.

It can be observed that most of China’s wind resources are ideally located in areas with very low population with the exception of the coastal areas. China is well aware of the country’s wind power potential. Wind power in China registered a record level of expansion recently, and has doubled its total capacity every year since 2004. [11]

The wind industry today is becoming one of the world’s fastest growing energy sectors, helping to satisfy global energy demands and offering the best opportunity to unlock a new era of environmental protection and to start the transition to a global economy based on sustainable energy. China with its large wind potential and the problems faced by its heavy reliance on fossil fuels has also heavily invested into the wind energy market. Figure 1 below shows the development of China’s installed wind capacity during the past five years.

In 2010 China’s total power capacity was estimated at 978.2GW with renewable wind power capacity reaching 44.8GW.[13] Chinas wind power capacity thus makes up 4.5 percent of its total capacity and has now surpassed the US wind power capacity. During the 2005–2010 period, wind power grew 36-fold from over 1GW in 2005.

Wind Power related Laws, Regulations and Policies

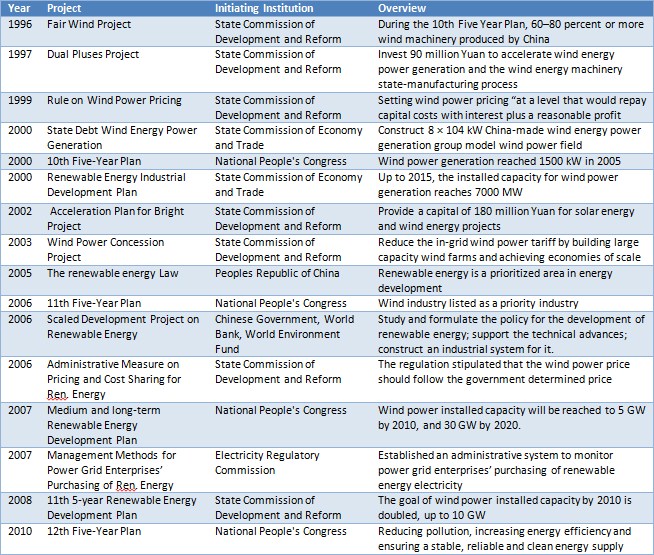

China’s grid-connected wind power can be traced back to the 1980s when the first pilot wind farm was established in Rongchen City located in East China’s Shandong Province. However it was only in the 1990’s when policies regarding wind power energy emerged with the 8th Five Year plan where wind energy was specifically mentioned for the first time. The 8th Five Year Plan was followed by a large amount of policies and legislation supporting wind energy especially during the past decade. A list of wind policies and legislation regarding wind power can be found below in Table 1. Notice that policies indirectly affecting the wind energy sector such as carbon credit policies or carbon emission policies for example have not been included.

Reflecting back on the growth of China’s wind capacity (Figure 3), whilst investigating China’s legislation and policies in relation to the wind energy sector, it becomes evident that the rapid growth of China’s wind power is strongly dependent on government intervention.

In 1999 the National Development and Reform Commission released an official statement setting wind power pricing ‘at a level that would repay capital costs with interest plus a reasonable profit’ [18]. This was followed by a series of government investments into the construction of wind farms including the first specific target by the 10th five year plan of 1500kw of wind power capacity that was to be reached by 2005.

Power Concession Program (2003)

In 2003 the Wind Power Concession Program was implemented with the aim to acquire investors for wind farms over 50MW through concession bidding. Whilst at first the bidder who agreed to build a wind farm with the lowest concession credit this was later revised so that the electricity price was given 40 percent of the total weight in deciding the winning bids.[19] Under the wind power concession program the provincial grid company must sign a power purchase agreement with the winners of the concession auctions. This is the first time it emerged that grid power companies are forced to so and became official law with the passing of the Renewable Energy Law in 2005.

Requirements of Local Content (2005)

The requirements of local content law passed in 2005 increased the percentage of parts that have to be locally sourced to be eligible for the wind concession program to 70 percent up from an initial 50 percent. The result of this was clearly noticeable with China now having three wind power manufacturers that are competing with the world’s top ten.

The Renewable Energy Law (2005)

On 28 February 2005, the Renewable Energy Law was passed in the 14th session of the 10th NPC Standing Committee. The Law of Renewable recognises the significance of renewable energy development in China stating that: “In order to promote the development and utilisation of renewable energy, improve the energy structure, diversify energy supplies, safeguard energy security, protect the environment, and realise the sustainable development of the economy and society, this Law is hereby prepared” [20]. The Renewable Energy Law put forward a comprehensive renewable energy policy framework, and institutionalised a number of policies and instruments for China’s renewable energy development and utilisation bringing the exploitation and use of renewable energy to a “new strategic height”. [21] “The Renewable Energy Law is umbrella legislation where the details on the implementation are supported by various ministerial regulations and measures.” [22] Some of most relevant directives for the wind industry include: The attribution of functions and responsibilities to the relevant government agencies (Art 4, 5), directives on setting indicative renewable energy targets (Art 7), directives on renewable energy planning based on targets set (Art 8), directions on technology acquisition (Art 10-12), an order for grid enterprises to enter into grid connection agreements with renewable energy enterprises (Art 14), direction that grid price power of renewable energy shall be determined by the price authorities of the State Council (Article 19), directives on a Government budget for the development and support of renewable energy sources (Art 24). Out of those the government’s investment into the renewable energy sector and the order for grid enterprises to enter into agreements with renewable energy enterprises are of fundamental importance for the wind energy sectors growth. Concretely, the order for grid enterprises to enter into agreements with renewable energy enterprises meant that power grid companies where required to sign a grid connection agreement with any state approved wind power generating company and purchase the full amount of wind power generated by it at a price set by the government. By the end 2006 National Development and Reform Commission had approved the construction of five wind farms with minimum capacity of 100 megawatts each.

Provisional Administrative Measure on Pricing and Cost sharing for Renewable Energy Power Generation (2006)

Shortly after the Renewable Energy Law was passed the National Development and Reform Commission issued the Provisional Administrative Measure on Pricing and Cost sharing for Renewable Energy Power Generation. The regulation creates the legal framework enabling the Government to set the price at which wind electricity has to be bought by grid companies.

Medium and Long-Term Development Plan for Renewable Energy in China (2007)

The Medium and Long-Term Development Plan for Renewable Energy established specific targets for the Renewables. By 2010 China aimed to raise the share of renewable energy consumption to 10 percent and by 2020 to 15 percent respectively. [23] Furthermore the policy document also specifies targets for various renewable energy sources as specified in Table 2 below. As we have previously observed, the targets are again based on the installed generating capacity rather than the actual amount of electricity supplied to the connected power grid.

The Medium and Long-Term Development Plan for Renewable Energy in China also establishes some national policies and measures. Those include the establishment of a sustainable and stable market demand for renewable energy; the improvement of the market environment including the construction and extension of grids; renewable power tariff’s and cost sharing policies; to increase the fiscal input and tax incentives and to accelerate technology improvement and industry development. [24] Under technological improvement we again observe that China aims to have the technology from within the country: “By 2010, a basic system of renewable energy technologies and industry will have been established, so that equipment capabilities based mainly on domestic manufacturing will have been established.” [25]

Management Methods for Power Grid Enterprises’ Purchasing of Renewable Energy Electricity (2007)

In June 2006, China’s Ministry of Finance issued the Tentative Management Method for Renewable Energy Development Special Fund, offering “additional measures to enhance support for renewable energy development”.[26] The policy includes assistance priorities, applications for assistance guidelines, their screening and approval, financial management, tests and control. Importantly, the policy has empowered the central government to provide financial assistance for the development of renewable energy resources including wind power.

The special fund provides grants and subsidies covering interest on loans, giving priority to the development and utilization of three major renewable energy sources: Renewable energy sources as high potential and promising oil substitutes, renewable energy sources related to heat supply and air conditioning for buildings, and renewable energy sources for power generation. [27] “More specifically, priority is given to the diffusion of solar and geothermal energy for heat supply and air conditioning for buildings, and to the diffusion fo application of wind, solar and marine energy for power generation.” [28]

Twelfth Five-Year Plan (2011-2015)

Energy policy in the 12th Five Year focuses on reducing pollution, increasing energy efficiency and ensuring a stable, reliable and clean energy supply. Before the release of the 12th Five Year Plan, China’s Director of the State Bureau of Energy Guobao Zhange emphasised that renewable energy resources will continue to be central to China’s energy policy and will be given even higher priority in the upcoming Five-Year Plan. [29]

On March 14 2011, China officially adopted its latest Five-Year Plan announcing a 11.4 percent renewable energy target for 2015 (up from 8.2 percent in 2009). This is in line with China’s pledge to acquire 15 percent of its energy from non-fossil fuels by 2020. Furthermore Energy consumption per unit of GDP is to be cut by 16 percent and Carbon dioxide emission per unit of GDP are to be cut by 17 percent. [30] Whilst the figures have been criticised for being too low[31], they are nevertheless expected to have a significant impact on the country’s energy portfolio balance as seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 6. China’s estimated sources of energy in relation to total energy production (Source: No. 32)

China’s head of the Energy Research Centre, Wenke Han, noted that under 12th Five Year Plan the investment into renewable resources will reach 470 billion USD.[33] The new five year plan also specifically mentions the introduction of smart grids and decentralised energy systems to China as the country currently faces problems to connect its renewable energy resources to its grid. Currently 30 percent of China’s built wind turbines are not producing energy as China is facing grid problems preventing them from being used for power production.

More generally the 12th five year plan aims to promote technological innovation in the energy sector such as decentralised energy system and clean coal; “to improve the macro framework to monitor the energy developments scientifically; to reform the pricing, tax and resource mechanism of energy gradually in order to foster an open and healthy market environment and to develop an improved policy and standard framework for sustainable energy developments”. [34]

China, in its struggle for Energy Security, has been seen exploring several paths to ensure the country will not be subject to an energy crisis in the future.

Themes of China’s Renewable Energy Laws and Policies

Based on the previously analysed policies, certain consistent themes in China’s policy making emerge that are relevant to wind power. These include the continuous adjustment of its renewable energy targets, concessions for the construction of wind farms including tax incentives and financial subsidies, low cost bonds and government grants, renewable energy price fixing by the government, guaranteed grid connection and purchase of energy, continuous increase of the requirements for local manufacturing and high local content renewables.

Problems of China’s Renewable Energy Policies and Legislation

Chinas wind energy policies have become a strong backbone for the wind energy industry within the country during the last decade. However, with the continuous evolution of the policies and the continuous adaption of new policies at various state levels, certain problems regarding China’s policy behaviour have begun to emerge.

Lack of Coordination and Consistency in Policy Making

One of the key issues with China’s renewable energy policies is the large number of government bodies issuing policies and regulations. Whilst we discussed mainly policies and laws issued by the State Commission of Development and Reform, the State Commission of Economy and Trade, the National People’s Congress and the Electricity Regulatory Commission there are still numerous additional local and provincial bodies that issue their own policies in support of the national policies. This results in a policy and legal environment which is not only difficult to oversee but also in an environment where policies diverge from each other.

“For instance, in order to reduce the investment cost in wind energy power plants, China canceled the tariff for importing wind energy power generators; while on the other side, the concerned sectors had been making active efforts to support the China-manufacturing process of wind energy power generation equipment implementing some model projects for the China-manufacturing process.” [35] A further example is the nullification of localization requirements outlined by the Requirements of Local Content policy stating that at least 70 percent of the wind turbine equipment needs to be produced locally in order for the government to be eligible for government support. In a major turnaround, the requirement was removed with the statement issued by the State Commission of Development and Reform in November 2009 abolishing the Requirement of Localization of Equipment Procurement on Wind Power Projects. [36] Such changes in policy direction have a negative impact on the policy environment as it creates a great amount of uncertainty. China seems to adapt or change its policies to be in line with what the government perceives as the right course of action at any given time which is not good for consistency.

Absence of Oversight

With the lack of coordination and consistency of Chinas Laws and Policies concerned with renewable energies comes the problem of oversight. With such a vast amount of policies on renewable energies it becomes increasingly difficult to keep track of all policy and legislative developments.

Weakness and Incompleteness in the Encouragement System

Whilst the legal frameworks for various incentives such as tax incentives for example are in place, their actual implementation is often weak. Su and Tsen note that many of the subsidies are symbolic rather than truly supporting an initiative. [37] An example of this is the taxation subsidies for renewable energies: “The actual taxation of most renewable energy projects are quite close to that of conventional energy, and some are even higher than that of conventional energy. This could not present the favorable conditions and policy for renewable energy. For instance, in according to the concerned favorable policies, RMB 0.25 yuan/(kW h) should be given to biomass energy power generation but this price is still about RMB 0.2 yuan/(kW h) higher than that of conventional power, plunging the biomass energy power generation into the bad at the very beginning.” [38] A further issue with the encouragement system is that it is often incomplete. Looking at wind power energy for example we find subsidies and incentives for the construction of wind power. However, just as important is the grid extension so those wind farms can be connected to the grid, and yet, there is a great lack of incentives in this area resulting in wind farms that have the capacity on paper but don’t produce any energy.

Lack of Innovation in Regional Policy

China is blessed with enormous territory giving it a vast amount of opportunities to generate wind power in low population areas. However, there are significant differences between different provincial states as well as between east and west and north and south. China’s current policy and legal framework does not account for those regional differences and is currently following a one model fits all philosophy. “The regional renewable energy’s comparative advantage and industrialized competitive advantages have not been defined in accordance with the actual local conditions, which enormously hinders the development of renewable energy industry.” [39]

Barriers for Wind Energy

The New Promotion Renewable Energy Law of 2005 is the most recent and perhaps the most comprehensive body of policy that intends to promote renewable energy in China. Yet, generation from renewables remains low where its expansion has been disrupted and delayed by a few types of obstacles, i.e. financial, innovation, institutional, technical. In the following paragraphs various barriers hindering the development of the wind power as an energy source will be discussed.

High Cost of Developing Renewable Wind Energy

The high cost of renewable energy by comparison with coal-fired generation continues to be a significant barrier. “Modern renewable energy technologies are relatively nascent within the power sector, have yet to become fully-commercialised and unlike conventional energy technologies do not benefit from the decades of institutional and organisational adaptation.” [40] This problem is particularly severe in China as the Government has been motivated to keep electricity prices low in support of GDP growth. This policy directly conflicts with promoting renewable energies and bringing the costs of them to parity with conventional sources of energy.

A further contributor to cost is china’s lack of technical level in most renewable energy industries despite the government’s research and development grants. This forces China to import the technologies from other countries resulting in higher equipment costs. In the case of wind turbines only five years it was found that developers of wind technologies in China had to import equipment from overseas at a cost 60 percent higher of that if it had been purchased locally. [41] However, with the massive growth of the Chinese wind we have seen that Chinese wind companies have increasingly been managed to build and acquire their own technology portfolio and are continuing to do so.

The high up-front costs for wind energy are also a substantial barrier for the renewable energy resource. Investors face a significantly higher up-front cost with wind energy than it is the case with traditional fossil based energies.

Grid Connection Problems

Currently 30 percent of China’s built wind turbines are not producing energy as China is facing grid problems preventing them from being used for power production. This is both a problem of policy and technology. The 12th Five Year Plan now specifically mentions the development of smart grids so Wind power can effectively be used as a source of power. However, the development of smart grids is highly costly and time consuming endeavour.

Risks and Uncertainties

From an investors perspective the renewable energy market is that of high risk. Most renewable energy technologies fall either in the Research and Development stage, in the pilot and demonstration stage, or in the early commercialisation stage with wind turbines currently classified to being in the early commercialisation stage. [42] Furthermore Investors are mindful of the market entry risks that the renewable energy market bears in China. The Chinese energy market is dominated by conventional energy enterprises which are in a highly advantageous position in regards to competing with renewable energy companies in terms of size, resource price and market penetration. Similarly the grid companies are often not willing to accept electricity generated from renewable energy sources due to their higher costs both due to production costs and lack of economies of scale for the grid networks.

The lack of technology needed to build large wind turbine motors or grid connection technology does not only result in high costs but also in high risks for Investors. So are for example China’s ambitious plans to expand into the western wind markets challenged by the lack of technology limiting the size of wind turbines. Whereas the mainstream wind turbines in the European market are as large as 1.5MW per unit; China does not yet have the capacity to manufacture wind turbines of more than 1MW. [43] The lack of grid connection technologies is a further example of technological risk as investors face the scenario of having wind turbines ready for power generation but unable to do so because they can’t be connected to the grid. As previously mentioned an estimated 30 percent of China’s built wind turbines are not producing energy as China is facing grid problems preventing them from being used for power production.

China’s Renewable Energy Law which took effect in January 2006 was the first state level policy passed with the sole purpose of promoting renewable energies. It’s implementation was however heavily debated. Specific mechanisms and methods for premium transfer and grid-connection cost management have not yet been implemented and neither have specific and consistent plans for the use of the China’s special fiscal fund for renewable development implemented. [44] Xilang et al. note that the debates over feed-in tariff and public bidding seem to be both persistent and inconclusive. Further policy associated risk is that of the policy driven market. With the renewable energy sector’s survival dependent on Chinese policies their consistency and implementation greatly affects the market of renewable resources and play an essential role in investor decisions. All these policy uncertainties mentioned add risk for the investor considering the Chinese wind energy sector.

Conclusion

China has been experiencing a rapid increase in energy consumption during the past decades and with it came issues such pollution, greenhouse gas emissions and energy security. The development of renewable energy sources is essential for China to tackle those issues with wind power bearing great potential as one such alternative renewable resource. Wind power has seen strong government support in China and has made leaps in installation capacity with wind power having grown 36-fold during from slightly over 1GW to 44.8GW capacity during the 2005 – 2010 period.

We observed a large amount of policies in the renewable energy field that are concerned with wind power. China has been continuously increasing its renewable energy targets, issued policies regarding concessions for the construction of wind farms including tax incentives and financial subsidies, regarding renewable energy price fixing by the government, regarding guaranteed grid connection and the definitive purchase of power created by wind farms and regarding high local manufacturing content. Based on the great potential of wind power in china and the strong government support it is expected that the industry will continue to grow at a substantial rate adopted its. In the 12th Five-Year Plan China announced that it plans to have renewable resources make up 11.4 percent of its energy portfolio in 2015. Wind is expected to play a substantial part in China’s energy portfolio diversification with a planned 100GW capacity of wind energy by 2015, a tenfold increase since 2010.

However, with the vast amount of policies issued by China regarding renewable energies and wind power certain problems started to emerge. A lack of coordination and consistency in China’s policy making was found. Example of this included the implementation and cancellation on tariffs for importing wind energy power as well as the nullification of localization requirements. Such changes in policy direction have a negative impact on the policy environment as it creates a great amount of uncertainty. China seems to adapt or change its policies to be in line with what the government perceives as the right course of action at any given time which is not good for consistency. Further issues identified where the lack of completeness of renewable energy promotion policies and the lack of innovation in regional policy.

Furthermore various barriers to the effective development of wind power as a renewable energy source where identified. These included the high development and up-front costs for wind turbines, grid connection problems and risks and uncertainties for investors. Never the less, despite the policy issues and barriers identified wind energy is expected to continue to grow substantially within the next decade as one of China’s key renewable resources.

References

1 Feng Wang et al, China’s renewable energy policy: Commitments and challenges, (2010) 38(4) Energy Policy 1872-1878.

2 Bing Jiang et al., China’s energy development strategy under the low carbon economy, Energy (2010) 35(11) 4257-4264.

3 Simon Rogers and Lisa Evans, World carbon dioxide emissions data by country: China speeds ahead of the rest, The Guardian, 31 January 2011.

4 Anna Petherick, Emission Markets out East, (2011) 1 Nature 138-139.

5 Bing Jiang et al., China’s energy development strategy under the low carbon economy, Energy (2010) 35(11) 4257-4264.

6 International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2010, Executive Summary.

7 Bing Jiang et al., China’s energy development strategy under the low carbon economy, Energy (2010) 35(11) 4257-4264.

8 Ibid.

9 International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2010, Executive Summary.

10 Xia Changliang et al., Wind energy in China: Current scenario and future perspectives, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (2009) 13(8) 1966-1974.

11 Ibid.

12 Centre for Global Energy Studies, Quarterly Oil Demand Report, July 2011.

13 Ibid.

14 Zhang Peidong et al., Opportunities and challenges for renewable energy policy in China, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (2009) 13(2) 439-449.

15 The Renewable Energy Law (People’s Republic of China) National People’s Congress Standing Committee, 28 February 2006.

16 Renewable Energy in China, National Renewable Energy Labaratory (2004).

17 Qiang Wang, Effective policies for renewable energy – the example of China’s wind power – lesson’s for China’s photovoltaic power, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (2010) 14(2) 702-712.

18 Ibid.

19 The Renewable Energy Law (People’s Republic of China) National People’s Congress Standing Committee, 28 February 2006.

20 Xiliang Zhang et al., A study of the role played by renewable energies in China’s sustainable energy supply, Energy (2010) 35(11) 4392-4399.

21 Jack Su and Kevin Tsen, China Rationalizs Its Renewable Energy Policy, Energy (2010).

22 Medium and Long Term Development Plan for Renewable Energy in China, National Development and Reform Commission, People’s Republic of China (2007).

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Ni Chunchun, China’s Wind-Power Generation Policy and Market Developments, The Institute of Energy Economics (2008).

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 ‘China’s 12th Five-Year Plan’, APCO, 10 December 2010.

29 ‘Ibid.

30 Sam Geal et al. China’s Green Revolution: China’s Green Revolution: Energy, Environment and the 12th Five-Year Plan (2011) Chinadialogue.

31 ‘China’s 12th Five-Year Plan’, APCO, 10 December 2010.

32 Zhen-Yu Zhao et al., ‘Impacts of renewable energy regulations on the structure of power generation in China – A critical analysis’ (2011) 36,1 Renewable Energy, 24-30.

33 Jack Su and Kevin Tsen, China Rationalizs Its Renewable Energy Policy, Energy (2010).

34 Zhang Peidong et al., Opportunities and challenges for renewable energy policy in China, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (2009) 13(2) 439-449.

35 Jack Su and Kevin Tsen, China Rationalizs Its Renewable Energy Policy, Energy (2010).

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Judith Cherni et al., Renewable energy policy and electricity market reforms in China, Energy Policy (2007) 35(7) 3616-3629.

40 Ibid.

41 Xiliang Zhang et al., A study of the role played by renewable energies in China’s sustainable energy supply, Energy (2010) 35(11) 4392-4399.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

Pingback: China Struggling to Respond to US Energy Revolution « 2012 Hội nhập Phát triển